History of Jefferson County

Jefferson County has a rich and extensive history. Read below to learn about some of the themes and events that shaped our county. You can also click Here to read more about historic figures in Jefferson County.

16th – 18th centuries

Native American Habitation

The Mound Builders, also known as the Adena, were the first known settlers in present-day West Virginia’s Eastern Panhandle of Berkeley, Jefferson, and Morgan counties. Remnants of the Mound Builders’ civilization have been found throughout West Virginia, with a high concentration of artifacts in Moundsville, WV, which is also the home of The Grave Creek Indian Mound, one of West Virginia’s most famous historic landmarks.

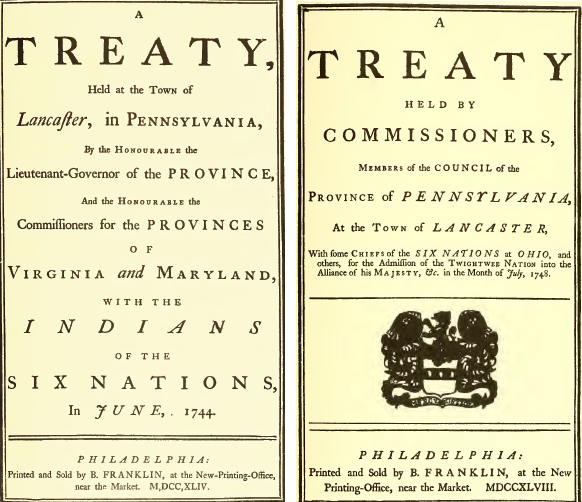

According to missionary reports, several thousand Hurons occupied present-day West Virginia during the late 1500s and early 1600s. During the 1600s, the Iroquois Confederacy (then consisting of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, Oneida, and Seneca tribes) drove the Hurons from the state. The Iroquois Confederacy was headquartered in New York and was not interested in occupying present-day West Virginia. Instead, they used it as a hunting ground during the spring and summer months.

During the early 1700s, the Eastern Panhandle was inhabited by the Tuscarora. They eventually migrated northward into New York and, in 1712, became the sixth nation to be formally admitted into the Iroquois Confederacy. The area was also used as a hunting ground by several other Indian tribes, including the Shawnee, the Mingo, and the Delaware.

18th century

The American Revolution

In 1744, Virginia officials purchased the Iroquois title of ownership to what is now West Virginia in the Treaty of Lancaster. The treaty reduced the Iroquois Confederacy’s presence in the state. During the mid-1700s, the English indicated to the various Indian tribes residing in the region that they intended to settle the frontier. The French, on the other hand, were more interested in trading with the Indians than settling in the area. This influenced the Mingo to side with the French during the French and Indian War (1755-1763). Although the Iroquois Confederacy officially remained neutral, many in the Iroquois Confederacy also allied with the French. Unfortunately for them, the French lost the war and ceded their North American possessions to the British.

England’s King George III feared that more tension between Native Americans and settlers was inevitable. In an attempt to avert further bloodshed, he issued the Proclamation of 1763, prohibiting settlement west of the Allegheny Mountains. The next five years were relatively peaceful on the frontier. However, many land speculators violated the proclamation by claiming vast acreage in western Virginia. In 1768, the Iroquois Confederacy and the Cherokee signed the Treaty of Hard Labour and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, relinquishing their claims on the territory between the Ohio River and the Alleghenies to the British. With the frontier now open, settlers, once again, began to enter into present-day West Virginia.

During the American Revolutionary War (1776-1783), the Mingo and Shawnee, headquartered at Chillicothe, Ohio, allied themselves with the British. In 1777, a party of 350 Wyandots, Shawnees and Mingos, armed by the British, attacked Fort Henry, near present-day Wheeling. Nearly half of the soldiers manning the fort were killed in the three-day assault. The Indians then left the area celebrating their victory. For the remainder of the war, smaller raiding parties of Mingo, Shawnee, and other Indian tribes terrorized settlers throughout northern and eastern West Virginia. As a result, European settlement throughout present-day West Virginia, including the eastern panhandle, came to a virtual standstill until the war’s conclusion.

John Lederer, a German physician and explorer employed by Sir William Berkeley, colonial governor of Virginia, was the first Englishman to set foot in present-day Jefferson County. He explored the region in 1669. In 1707, Louis Michel made a map of the future site of Jefferson County and, in 1712, Christopher Baron de Graffenreid entered into present-day Jefferson County during his expedition up the Potomac River.

The first permanent English settlement in present-day Jefferson County was attempted in the Shepherdstown area in 1719, but no official records were kept of the settlers’ names. Their presence is suggested by a letter written in 1719 from the residents of “Potomoke” (now known as Shepherdstown) to the Philadelphia Presbyterian Synod requesting that a minister be sent to the town.

In 1727, several German immigrant families founded the town of New Mecklenburg, renamed Shepherdstown in 1798 in honor of Captain Thomas and Elizabeth Shepherd. Thomas Shepherd had received a patent on October 3, 1734 for much of the land in that area and was the town’s leading citizen until his death in 1776. Other early settlers included John and Isaac Van Meter who obtained grants to large tracts of land in the county in 1730.

Both Shepherdstown (then known as Mecklenburg) and Romney (in Hampshire County) were chartered by the Virginia General Assembly on December 23, 1762. However, Romney claims that it is the oldest town in the state because its earliest settlers arrived before Shepherdstown’s earliest settlers arrived. However, it is difficult to substantiate Romney’s claim, and both towns claim the title of oldest town in the state.

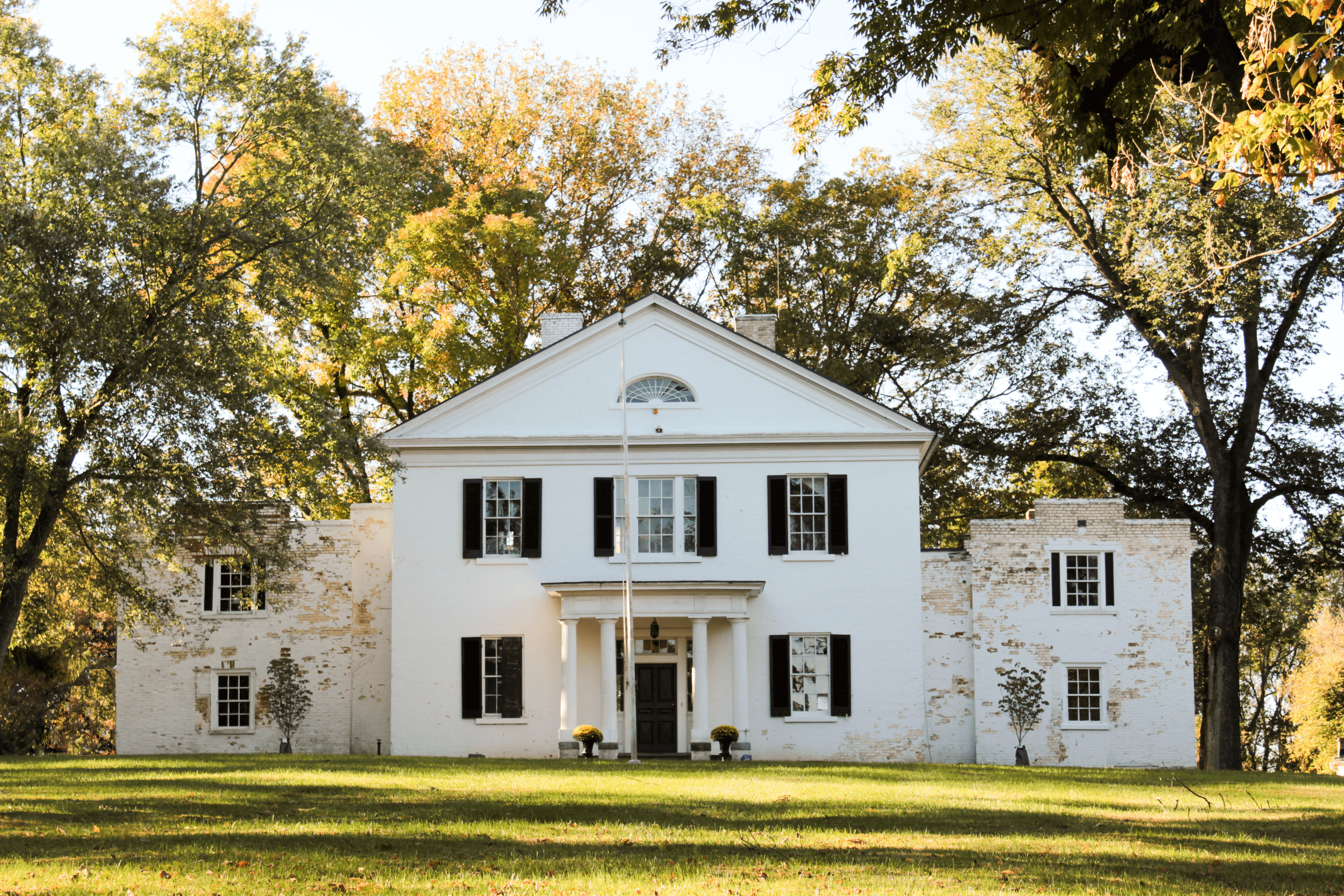

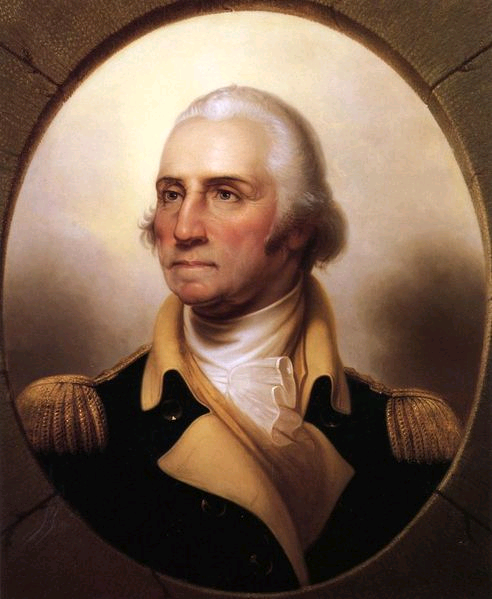

As mentioned previously, in 1748 sixteen year old George Washington surveyed the eastern panhandle region for Lord Fairfax. Washington was impressed with the region and, in 1750, bought land along Bullskin Run. Through the years, he continued to acquire more land in the area, and, at one point, owned nearly 2,300 acres in the Eastern Panhandle. Washington’s half brother, Lawrence, also owned land in the county, and when he died without any heirs in 1752, he left much of it to his brothers: George, Samuel, John Augustine, and Charles. Samuel Washington’s home, known as Harewood, was located in present-day Jefferson County. The home featured an exquisite marble mantelpiece that had been given to George Washington as a gift by General Marquis de Lafayette. George Washington gave it to Samuel as a present. Harewood was also the site of Dolley Payne Todd and James Madison’s marriage.

In 1755 General Edward Braddock led a British expeditionary force through what is now Jefferson County on his way to his ill-fated battle with the French at Fort Duquesne during the French and Indian War. The route of his march was through parts of what is now Jefferson County. Braddock’s death and his army’s defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela was a major setback for the British in the early stages of the war with France.

When the American Revolution began, Virginians Daniel Morgan of Frederick County and Hugh Stephenson of Berkeley County (later Jefferson County) organized two regiments of Virginia volunteers to join General Washington’s forces in Massachusetts. Stephenson and Morgan, both veterans of Lord Dunmore’s War and friendly rivals, organized their regiments quickly in an attempt to reach General Washington first. Morgan’s regiment was the first to arrive. Stephenson’s regiment was easily distinguished on the field of battle. They embroidered Patrick Henry’s famous slogan “Liberty or Death” on their shirts. Tragically, many of the Berkeley/Jefferson County volunteers where present when the British captured Forts Washington and Lee. Many of the prisoners died after being treated harshly.

One of the most famous American Revolutionary War leaders resided in present-day Jefferson County prior to the war. Horatio Gates (1729-1806), General Washington’s second in command, lived at “Traveler’s Rest” near Kearneysville prior to the war.

James Rumsey was another famous resident of present-day Jefferson County. He lived in Shepherdstown and was the first man to propose using steam instead of wind to propel vessels. He built a steamer and sailed it on the Potomac River in the presence of George Washington and others on December 3, 1787, twenty years before Robert Fulton, who is generally regarded as the inventor of the steam boat, made his first successful steam voyage. Rumsey patented his invention and traveled to London in 1790 in an attempt to find investors willing to finance the construction of additional steam ships. Several ventures failed, primarily due to poor workmanship on the steam engines. He remained in London for nearly two years. On December 20, 1792, he made a presentation explaining his invention to the Society of Mechanic Arts in London. During the presentation, he burst a blood vessel and died the next morning. During his time in London, Rumsey met Robert Fulton who later modified Rumsey’s design and made steam navigation a success.

Shepherdstown was also the home of West Virginia’s first newspaper, the Potomak Guardian and Berkeley Advertiser. It began publication in 1790 and was owned by Nathaniel Willis. Charles Town, Jefferson County’s current seat, was chartered by the Virginia General Assembly in October 1786. It was named in honor of Charles Washington, George Washington’s youngest brother. Charles Washington moved to the area in 1780. His home, known as “Happy Retreat,” was a favorite rest stop for the wealthy and famous. Charles Town was laid out on eighty acres of land owned by Charles Washington

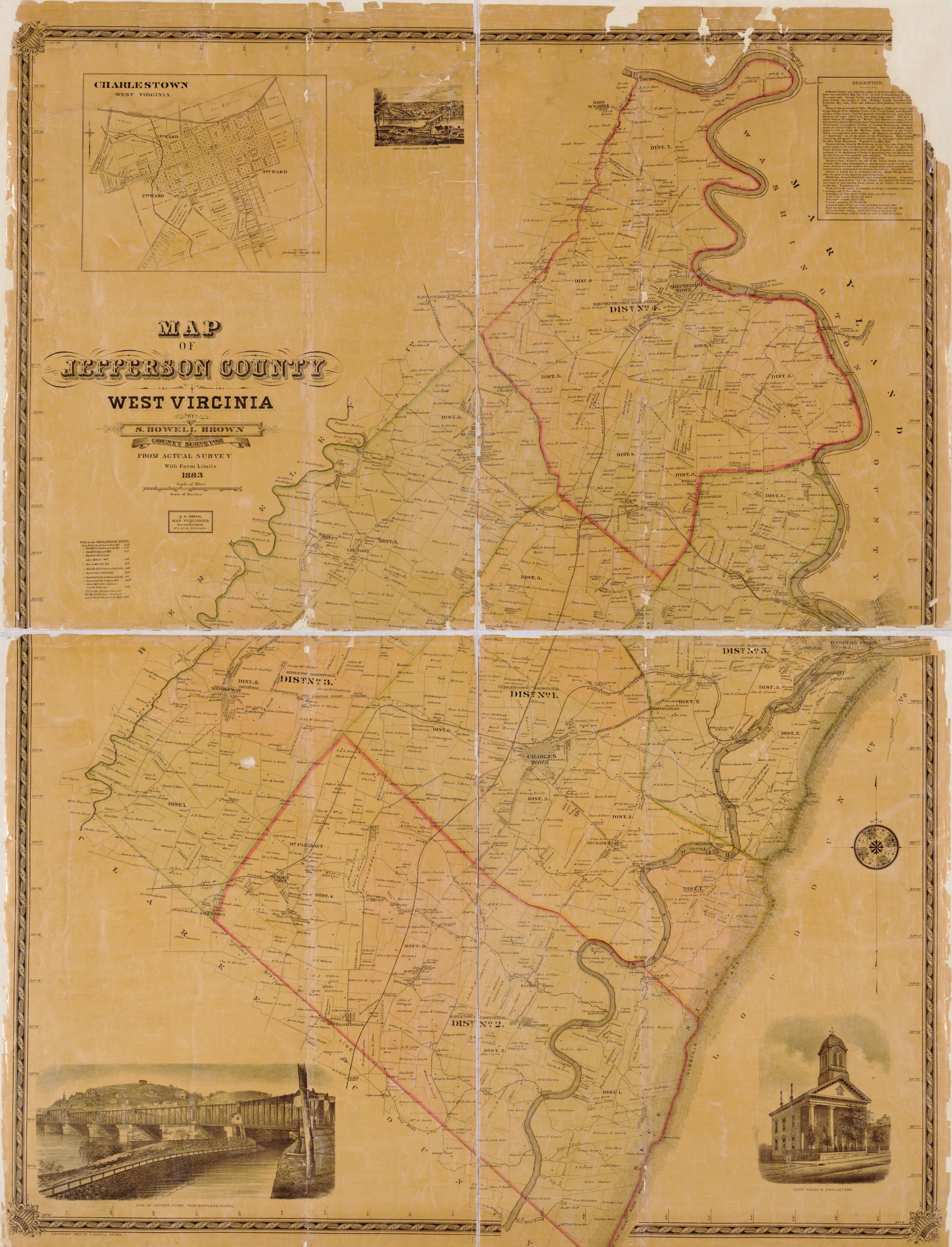

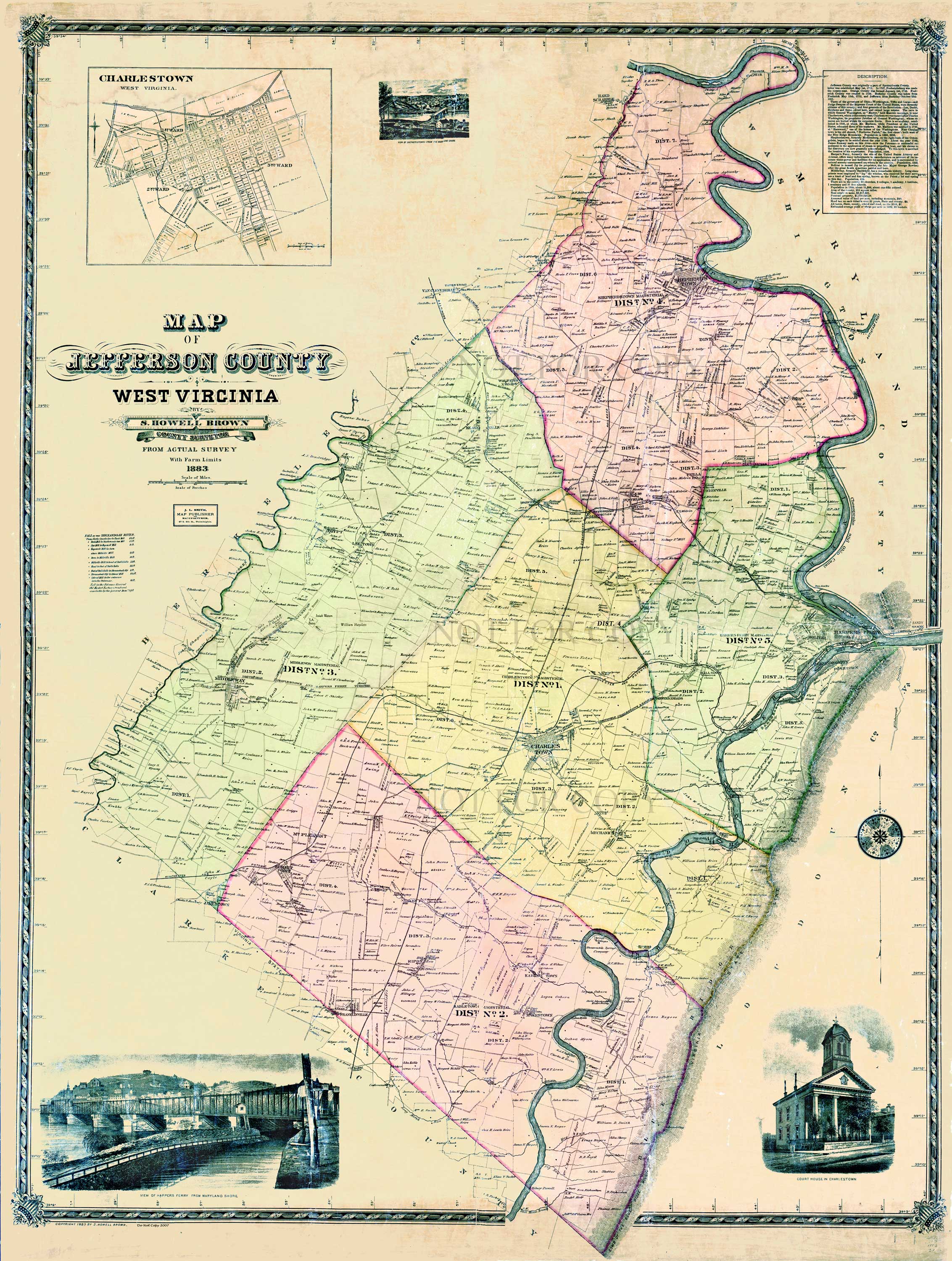

Jefferson County was created by an act of the General Assembly on January 8, 1801, from parts of Berkeley County. It was named in honor of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), who was then President-elect of the United States. One of America’s greatest statesmen, Thomas Jefferson was born in Shadwell, Virginia on April 2, 1743 and graduated from William and Mary College in 1762. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1767. He served as a member of the Colonial House of Burgesses from 1769 to 1774 and again in 1782; a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1775, 1776, and again from 1782 to 1785; drafted the Declaration of Independence on July 2, 1776; served as Governor of Virginia from 1779 to 1781; and was appointed minister to France in 1785. He served in that capacity for three years. He was then the first Secretary of State during George Washington’s Administration, was elected Vice-President of the United States during John Adams’s Administration, and was elected the 3rd President of the United States in 1801. He was re-elected in 1805 (serving from 1801 to 1809).

19th century

The Nineteenth Century

One of Jefferson County’s highest priorities during the early 1800’s was improving the county’s roads and waterways. By the 1830s, a turnpike had been constructed that connected Shepherdstown to Middleway and a stage line ran from Washington D.C. to Leesburg (then part of the county). The early 1830s also saw the construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to Harper’s Ferry and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the canal’s competitor, arrived a year after the canal opened in 1834. In 1835, the Winchester and Potomac Railroad linked the county with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at Harpers Ferry. The new roads, railroads, and canals opened the Jefferson County area to economic expansion.

Click Here to read about the 1860 presidential election in Jefferson County!

19th Century

John Brown's Raid

(Source: The Confederate Military History, Volume 3, Chapter II. Volume written by Jed. Hotchkiss)

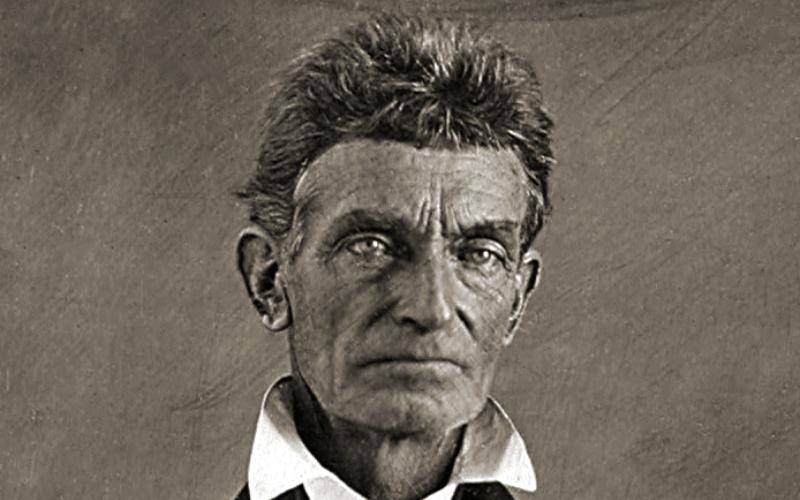

In the winter of 1857-58, John Brown, who had been a leader in and a promoter of lawlessness during the troubles in Kansas–undertaken, as he himself confessed, for the purpose of inflaming the public mind on the subject of slavery, that he might perfect organizations to bring about servile insurrections in the slave States—-collected a number of young men in that territory, including several of his sons, and, with the use of funds and arms that had been furnished for his Kansas operations, placed these men under military instruction, by one of their number, at Springdale, in Iowa. In the spring of 1858 he took these men to Chatham, in Canada West, where, on the 8th of May, he assembled a “provisional constitutional convention,” made up of those he brought with him and a number of resident free negroes. On the day of its assembling, this convention adopted a “provisional constitution and ordinances for the people of the United States,” the preamble of which began: “Whereas slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion …. Therefore, we, citizens of the United States and the oppressed people who . . . are declared to have no rights which the white man is bound to respect . . . ordain and establish for ourselves the following provisional constitution and ordinances, the better to protect our persons, property, lives and liberties, and govern our actions.” On the 10th, after appointing a committee with full power to fill all the executive, legislative, judicial and military offices named in the constitution adopted, this convention adjourned, sine die, and Brown took his Kansas party to Ohio, where he disbanded them subject to call, but sending his Capt. John E. Cook, of Connecticut (who was subsequently executed), to stay at Harper’s Ferry, Va., and make himself familiar with the surrounding country and its citizens, and especially with the negro slaves, for the information of his leader.

Brown, under the assumed name of Isaac Smith, appeared in the neighborhood of Harper’s Ferry about the 1st of July, 1859, and there is evidence to show that he extended his examination of the country for future strategic purposes, as far up the Shenandoah valley as Staunton, concealing his purposes by giving out that he was a farmer from New York, with his two sons and a son-in-law, desiring to rent or purchase land. Soon after his arrival at Harper’s Ferry he rented the small Kennedy farm in Maryland, some four and a half miles from Harper’s Ferry, where he did some little farming, and, to explain his secret movements, said he was accustomed to mining operations, and expected to find valuable mineral deposits in that mountain region. In the meantime he kept two or three of his party, under assumed names, at Chambersburg, Pa., who there received arms, ammunition. and other military stores, which had been collected for use in Kansas, and forwarded them from time to time to Brown’s habitation.

On October 10, 1859, from “Headquarters War Department, Provisional Army, Harper’s Ferry,” John Brown, commander-in-chief, issued his “General Order No. I,” organizing “the divisions of the provisional army and the coalition,” providing for company, battalion, regiment, brigade and general staff organization. It is probable that at the time of issuing this order Brown had with him, at the Kennedy farm, his whole band of followers, including his spy Cook, and there formulated his final plans of invasion; and that soon thereafter he removed to a schoolhouse nearer Harper’s Ferry, the hundreds of carbines, pistols, spears or pikes, and a quantity of cartridges, powder, percussion caps, and other military supplies, that he had gathered for arming the negroes when they rose to insurrection in response to his call and movements.

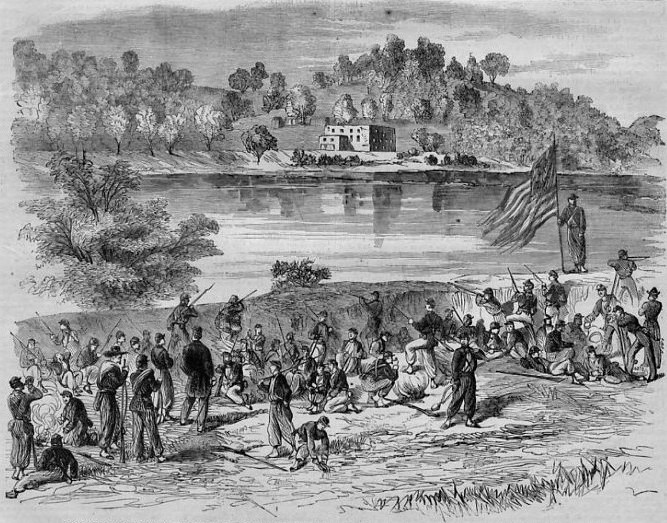

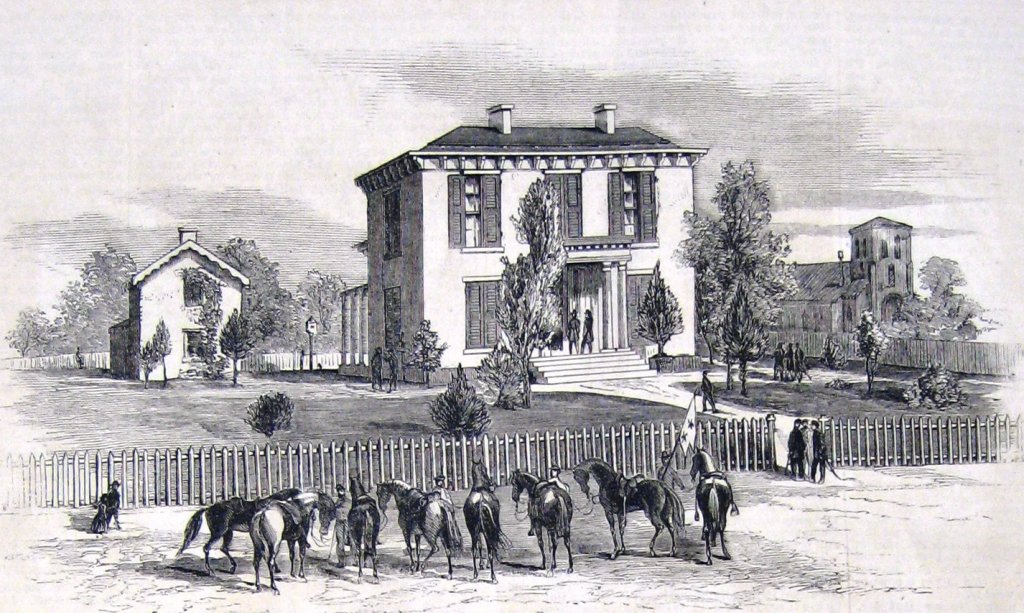

About 11 p.m., Sunday, October 16, 1859, Brown, accompanied by 14 white men from Connecticut, New York, Ohio, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Maine, Indiana and Canada, and 5 negroes from Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York, some 20 insurgents, all fully armed, crossed the Potomac into Virginia at Harper’s Ferry, overpowered the watchmen at the Baltimore & Ohio railroad bridge, the United States armory and arsenal near the Baltimore & Ohio, and the rifle factory above the town on the Shenandoah, and placed guards at those points and at the street corners of the town. Brown established himself in the thick-walled brick building at the armory gate, one room of which was the quarters of the watchman and the other contained a fire-engine; he then sent six men, including the spy Cook, under Captain Stevens, to seize the principal citizens in the neighborhood and incite the negroes to rise in insurrection. This party broke into the house of Col. L. W. Washington, about five miles from Harper’s Ferry, about 1:30 a. m. of the 17th, and forced him and four of his servants to accompany them to Harper’s Ferry, he in his own carriage and followed by one of his farm wagons, which they seized. On their way back, at about 3 a.m., they captured Mr. Allstadt and six of his servants, placing arms in the hands of the latter. On reaching Harper’s Ferry, Cook and five of the captured slaves were sent with Colonel Washington’s four-horse wagon to bring forward the arms, etc., deposited at the schoolhouse in Maryland.

In the meantime Brown halted, for a time, an eastbound passenger train on the Baltimore & Ohio, one of his men killing the railroad guard at the bridge; he also captured, as they appeared on the streets in the early morning, some 40 citizens of Harper’s Ferry, whom he confined, with Messrs. Washington and Allstadt, in one room of the gate or engine house which he had selected as his fort or point of defense.

News of these occurrences spread rapidly, and citizens and citizen soldiery, with arms, hastened from all the surrounding parts of Virginia and Maryland to resist this high-handed invasion of their homes and States. About 11 a.m., of the 17th, the Jefferson Guards, from Charlestown, arrived, soon followed by the Hamtramck and the Shepherdstown troop, from Shepherdstown, and Alburtis’ company from Martinsburg. These, under the command of Col. R. A. Baylor, forced the insurgents within the armory enclosure, which they surrounded by a cordon of pickets. Brown then withdrew his men into the gate house, which he proceeded to loophole and fortify, taking with him ten of the most prominent of his Virginia and Maryland captives, which he termed “hostages,” to insure the safety of his band. From openings in the building the insurgents fired upon all white people that came in sight.

After sunset of the 17th, Capt. B. B. Washington’s company from Winchester, and three companies from Frederick City, Md., under Colonel Shriver, arrived; later came companies from Baltimore, under Gen. C. C. Edgerton, and a detachment of United States marines, commanded by Lieut. J. Green and Major Russell, accompanied by Lieut.-Col. R. E. Lee, of the Second United States cavalry (with his aide, Lieut. J. E. B. Stuart, of the First United States cavalry), who, happening to be at Arlington, his home, near Washington, had been ordered to take command at Harper’s Ferry, recapture the government armory and arsenal, and restore order. Colonel Lee halted the Baltimore troops at Sandy Hook, about a mile and a half east of Harper’s Ferry, directed the United States artillery companies (ordered from Fort Monroe) to halt in Baltimore, then crossed to Harper’s Ferry with the marines, disposed them in the armory grounds so as to prevent the escape of the insurgents, and awaited dawn of the 18th before attacking Brown’s stronghold, for fear of sacrificing the lives of the “hostages” in a midnight attack.

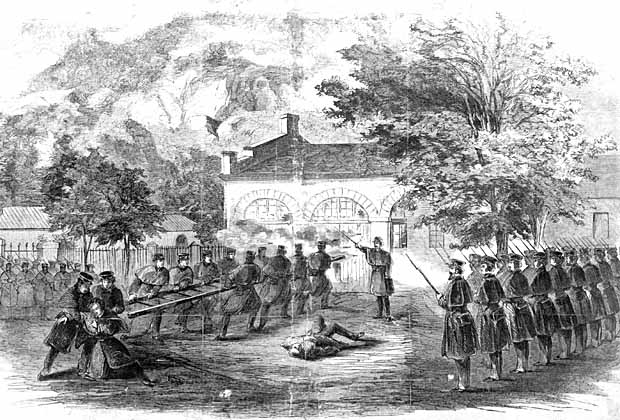

Soon after daylight of the 18th, after having posted the volunteer troops so as to completely invest the armory grounds, and prepared for an assault upon Brown’s fort by the marines, Lee, under a flag by Lieutenant Stuart, made a written demand upon Brown to surrender himself, his associates and the prisoners they had taken, with the assurance that “if they will peaceably surrender themselves and restore the pillaged property, they shall be kept in safety to await orders from the President …. That if he is compelled to take them by force he cannot answer for their safety.” Stuart was instructed to receive no counter propositions from Brown, and to say that if they accepted the proffered terms they must immediately give up their arms and release their prisoners. As Lee expected, Brown spurned the offered terms of surrender. At a given signal to this effect from Stuart, Lee ordered forward twelve marines, led by Lieutenant Green, that he had put under cover near the engine-house, three of them supplied with sledge hammers to break in the doors, to attack Brown’s party with bayonets, taking care not to injure the citizens held captive, nor the captured slaves unless they resisted. The storming party quickly attacked the doors, but Brown had barricaded them inside with the fire-engine and fastened them by ropes, so the sledges were of no avail. Lee then ordered forward reserves, with a heavy ladder for a battering ram, with which a portion of the door was dashed in and admission gained. Up to that time Brown’s fire had been harmless, but at the threshold one marine was mortally wounded. The others quickly ended the contest, bayoneting the insurrectionists that resisted, Lieutenant Green cutting down Brown with his sword. The whole affair was over in a few minutes, and the captured citizens and slaves were released. A party of marines under Stuart was then sent to the Kennedy farm, which captured pikes (said to have been over 1,000), blankets, tools, tents, and other necessaries for a campaign, which Brown had there stored. A party of Maryland troops secured from the schoolhouse, where Brown had deposited them, boxes of carbines and revolvers, and the horses and wagon of Colonel Washington, which Brown had sent there to bring his military supplies to Harper’s Ferry.

Colonel Lee in his official report to Col. S. Cooper, adjutant-general of the United States army, dated October 19th, stated, from information in papers taken from the insurgents and from their statements: “It appears that the party consisted of 19 men–14 white and 5 black. They were headed by John Brown, of some notoriety in Kansas, who in June last located himself in Maryland, at the Kennedy farm, where he has been engaged in preparing to capture the United States works at Harper’s Ferry. He avows that his object was the liberation of the slaves of Virginia and of the whole South, and acknowledges that he has been disappointed in his expectations of aid from the black as well as the white population, both in the Southern and Northern States. The blacks whom he forced from their homes in this neighborhood, as far as I could learn, gave him no voluntary assistance. The servants… retained at the armory, took no part in the conflict . . . and returned to their homes as soon as released. The result proves the plan was the attempt of a fanatic or madman, which could only end in failure; and its temporary success was owing to the panic and confusion he succeeded in creating by magnifying his numbers.”

Lee, by order of Secretary of War John B. Floyd, turned over to the United States marshal and to the sheriff of Jefferson county, Va., Brown and two white men and two negroes. Ten of the white men and two of the negroes associated with Brown were killed during the combat with them; one white man, Cook, escaped, but was subsequently captured and executed; and one negro was unaccounted for. The insurgents killed three white men, Mr. F. Beckham, the mayor of Harper’s Ferry, Mr. G. W. Turner, one of the first citizens of Jefferson county, and Private Quinn of the marine corps, and a negro railroad porter; they wounded eight white citizens and one of the marine corps. After this affair was over, great alarm was caused by a report, about sundown of the 18th, from Pleasant valley in Maryland, that a body of men had descended from the mountains. and was massacring the residents of that valley. Colonel Lee, though incredulous, promptly headed a body of marines and hastened to the locality named, only to find the alarm false.

In concluding his report, Colonel Lee expressed his thanks to Lieutenants Stuart and Green and Major Russell “for the aid they afforded me, and my entire commendation of the conduct of the detachment of marines, who were at all times ready and prompt in the execution of any duty. The promptness with which the volunteer troops repaired to the scene of disturbance, and the alacrity they displayed to suppress the gross outrage against law and order, I know will elicit your hearty approbation.” He enclosed to Cooper a printed copy of the provisional constitution and ordinances for the people of the United States, of which there was found a large number prepared for issue by the insurgents.

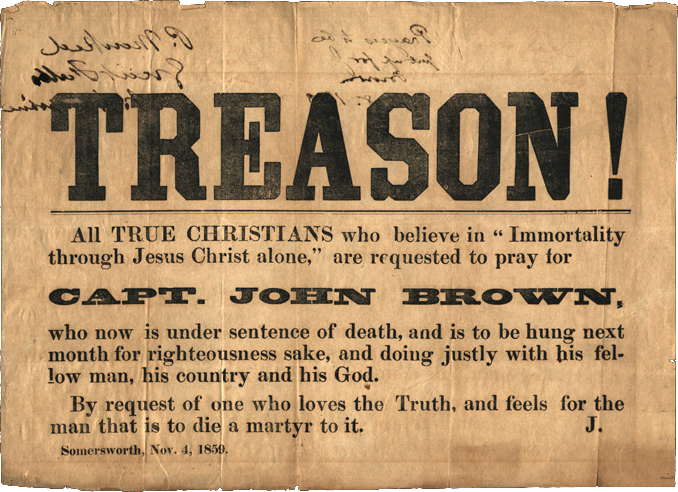

During the afternoon of October 18th, Gov. Henry A. Wise arrived at Harper’s Ferry and took precautions for the protection of Virginia and the execution of her laws, Brown, having been turned over to the civil authorities of Jefferson county, was brought to trial at Charlestown on the following Thursday, October 20th, because on that day began the regular fall session of the circuit court. A grand jury indicted him upon the charges of treason and murder. His prosecution was conducted before an impartial judge and jury by Hon. Andrew Hunter; he was defended by able counsel from Virginia and other States, including Hon. D. W. Voorhees, of Indiana, and was condemned and convicted. His trial lasted nearly a month, and, as Brown himself admitted, was fair and impartial. He was condemned to be executed on the 2nd of December. His counsel asked the Virginia court of appeals for a stay of execution, on pleas presented, but this was refused.

After the condemnation of Brown and his associates, fearing from published threats that an attempt might be made by Northern sympathizers to rescue them, Governor Wise ordered Virginia troops to Charlestown to guard the prisoners until after their execution. Toward the last of November about 1,000 were there assembled, among them the cadets of the Virginia military institute, under command of Col. F. H. Smith, the superintendent. Maj. T. J. Jackson, the famous “Stonewall” Jackson of the war, was present in command of the cadet battery. He witnessed the execution of Brown about midday, December 2, 1859. In a letter to his wife he wrote of Brown, “he behaved with unflinching firmness,” and of the execution: “My command was in front of the cadets, all facing south. One howitzer I assigned to Mr. Truehart, on the left of the cadets, and with the other I remained on the right. Other troops occupied different positions around the scaffold, and altogether it was an imposing but very solemn scene. I was much impressed with the thought that before me stood a man, in the full vigor of health, who must in a few moments enter eternity. I sent up the petition that he might be saved. Awful was the thought that he might in a few minutes receive the sentence, ‘Depart, ye wicked, into everlasting fire!’ I hope that he was prepared to die, but I am doubtful.”

On the day of Brown’s execution, bells were tolled and minute guns fired in many places in the North, and church services and public meetings were held for the purpose of glorifying his deeds and sanctifying the cause he represented, recognizing in him a martyr to the teachings of the abolitionists. Eventually his name became the slogan under which, as a battle hymn, the Northern troops invaded and overran the South.

19th century

The Civil War

Jefferson County was a center of activity during the Civil War, primarily because of its geographic location, especially its proximity to Washington, D.C. and the presence of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad within its borders. During the war, many of Jefferson County’s towns repeatedly changed hands, and each time they did the retreating forces typically destroyed the town’s main buildings and infrastructure.

Martin Robinson Delaney, born in Charles Town, worked with John Brown in the framing of Brown’s provisional constitution. During the Civil War, Delaney became the first African-American field officer. Most of the county’s residents sided with Virginia when the state seceded from the Union. Confederates from Jefferson County were heavily represented in the 12th Virginia Cavalry and the 2nd Virginia Infantry (Stonewall Brigade). Disenfranchised because of their support of the Confederacy, residents were unable to prevent the transfer of the court house from Charles Town to Shepherdstown in 1865. The county seat was returned to Charles Town in 1871, but relations between the two towns remained cool for decades (some might stay they still are).

It is interesting how Jefferson County, whose residents largely supported the Confederacy, became part of West Virginia. A statewide referendum was held in October 1861 to determine if a state Constitutional Convention should be held to form a new state. The referendum passed and a Constitutional Convention was held on November 26, 1861 in Wheeling. When determining the state’s boundaries, the delegates, realizing the importance of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad to West Virginia’s economic prospects, included the eastern panhandle in the state. When the West Virginia Constitution was put to a vote many of Jefferson County’s citizens did not even know that the question of whether to remain with Virginia or join the new state of West Virginia was being put to a vote. When the vote was taken the Union Army controlled the county and opened just two precincts for voting. Those known to be Confederate sympathizers were under house arrest, and were not allowed to vote. Jefferson County voted 248 for and two against joining the new state of West Virginia. At that time, the county had nearly 2,000 registered voters, but most of them were under house arrest.

19th century

Post-War Jefferson County

After the War, Virginia demanded that Berkeley and Jefferson counties be returned because they had not been a part of the original annexation approved by Congress. Many Jefferson and Berkeley county residents also expressed their desire to remain a part of Virginia. As the controversy over Berkeley and Jefferson counties continued, West Virginia’s state legislature, in January 1865, moved the Jefferson County seat from Charles Town to Shepherdstown, primarily because Shepherdstown’s residents were ardent supporters of becoming part of West Virginia. The Shepherdstown West Virginians even had a plan to form a new county to be called “Shepherd” if the citizens of the southern portion of the county did not comply with their wish to remain part of West Virginia. The controversy over Jefferson County’s location in West Virginia finally ended in 1866 after both the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives ruled in favor of West Virginia’s claim to the land. In an attempt to mollify those wanting the county to be returned to Virginia, the county seat was moved from Shepherdstown back to Charles Town.

When the county seat was moved from Shepherdstown, the town’s residents decided to establish a school in the now empty courthouse. The school was originally called the “Classical and Scientific Institute,” but its name was changed to Shepherd College in 1872. In exchange for state support, Shepherd College’s trustees offered the state free access to the courthouse building. The state accepted the offer and Shepherd College became a state normal school. In 1904, the college moved from the courthouse/McMurran Hall to a new building called “Knutti Hall,” named to honor its principal, J.G. Knutti.

19th-20th Centuries

Rural Free Delivery System

The first rural Americans to receive mail at home were West Virginians. The idea of a Rural Free Delivery system for farmers and others who lived far from cities and towns had been kicked around for several years during the administrations of both presidents Harrison and Cleveland.

It was the nation’s Postmaster General William Wilson who finally delivered on it. Wilson was serving as Postmaster in Cleveland’s administration when he picked Jefferson County to be the first in the nation to experiment with the system. It didn’t hurt that Wilson was a native son of the Jefferson County town of Charles Town. On October 1, 1896, five carriers began delivering mail in the region. Three operated out of Charles Town and one each from Halltown and Uvilla. The carriers were Harry Gibson, Frank Young, John Lucas, Keyes Strider, and Melvin Strider.

There is no official record of which one of these men is entitled to the honor of being the first Rural Free Delivery carrier in the United States. The Postal Service merely lists all of them as having carried the mail on October 1. Harry Gibson, though, always maintained that he carried mail unofficially for several days in August and September of that year to get acquainted with the work and to find out how long it took to make the rounds. Gibson retired from the service in 1919 and was succeeded by Vesta Watters Jones, the first woman mail carrier in West Virginia and one of the first in the entire United States. While Gibson delivered the mail by horseback, Jones began working the route in a Model T Ford. She remained on the job until she officially retired in 1961. There have only been four rural mail carriers to work the route of Gibson and Jones.

Jefferson County was the first but not the only region to try Rural Free Delivery. A short while after its beginnings in the county, similar routes were established in other states. In all, 15 routes were put into operation in various parts of the country in the month of October 1896. By June 1900, there were 1,214 RFD routes, serving an estimated 879,127 people in nearly every state. Six months later the number of routes had increased to 2,551. These provided mail service to almost 2 million Americans. Rural Free Delivery became a permanent postal service in 1902.

A 1903 movie clip by the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company shows a rural free delivery mailman standing waiting for the area mail to be delivered to him. As the film continues, a horse-drawn wagon marked “Rural Postal Delivery” passes the camera position. The mail is then handed to the waiting postman who boards a two-wheel wagon and drives away.

20th century

The Twentieth Century

The Niagara Movement. In February 1905, W.E.B. Dubois, John Hope, Monroe Trotter, Frederick McGhee, C. E. Bentley and 27 others met secretly in the home of Mary B. Talbert, a prominent member of Buffalo’s Michigan Street Baptist Church to adopt the resolutions which lead to the founding of the Niagara Movement, the cornerstone of the modern civil rights movement in America. The Niagara Movement renounced Booker T. Washington’s accommodation policies set forth in his famed “Atlanta Compromise” speech ten years earlier. The Niagara Movement’s manifesto was, in the words of Du Bois, “We want full manhood suffrage and we want it now…. We are men! We want to be treated as men. And we shall win.” They invited 59 well know African American businessmen to a meeting that summer in western New York. On July 11 thru 14, 1905 on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, twenty-nine men met and formed a group they called the Niagara Movement. The name came because of the location and the “mighty current” of protest they wished to unleash.

Du Bois was named general secretary and the group split into various committees. The founders agreed to divide the work at hand among state chapters. At the end of the first year, the organizations had only 170 members and were poorly funded. Nevertheless they pursued their activities, distributing pamphlets, lobbying against Jim Crow, and sending circulars and protest letters to President Theodore Roosevelt after the Brownsville Incident in 1906. In the summer of 1906 the Niagara Movement held its first meeting on American soil in Harpers Ferry, WV. Harpers Ferry was considered a symbol of freedom and a mode for progress in the struggles for equality. ‘Harpers Ferry was the site of John Brown’s raid and having the meeting there was intended to send a resounding message of just how serious these intellectuals were about confronting racism.

Despite the establishment of 30 branches and the achievement of a few scattered civil-rights victories at the local level, the group suffered from organizational weakness and lack of funds as well as a permanent headquarters or staff, and it never was able to attract mass support. After the Springfield (Ill.) Race Riot of 1908, Du Bois had invited Mary White Ovington, a settlement worker, and socialist to be the movement’s first white member. Soon other white liberals joined with the nucleus of Niagara “militants” and with Du Bois, founded the NAACP the next year. The Niagara Movement disbanded in 1910, with the leadership of Du Bois forming the main continuity between the two organizations.

The Miners’ Trials. Charles Town’s greatest claim to fame is perhaps the fact that the abolitionist John Brown was tried there for treason against Virginia in 1859. But what most people fail to realize is that in 1922 twenty-four men were brought to Jefferson County and placed in the old jail to face similar charges, this time for treason against the state of West Virginia. Two were actually tried in the same courthouse as Brown. William Blizzard, a coal miner and union official was acquitted and another miner, Walter Allen was convicted. Treason trials are extremely rare in the history of the United States but we had three that occurred here in Jefferson County in the span of roughly sixty years. More significant, however, is that when these trials are compared and contrasted with each other, they tell a story of immense importance in understanding our development as a nation.

The 1922 treason trials were the culmination of forces and events that had been building for two decades in the coal mining districts of West Virginia. Beginning in the late 1800’s the rich coal fields of the southern counties had begun producing vast quantities of coal. This coal was sold in markets where it competed with coal from the unionized mines of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Illinois. As a result, the United Mine Workers of America began trying to organize West Virginia’s miners in 1902 as a matter of survival.

Initially, the union focused on the New River fields but was more successful along Paint Creek and Cabin Creek in the Kanawha district near Charleston where they organized several thousand miners. Even so, within a short time, the union was broken on Cabin Creek and in order to keep them out, coal operators there imported hundreds of mine guards and Baldwin Felts Detectives to act as an armed barrier to any further attempts at organization.

What developed on Cabin Creek can only be described as a industrial police state where all roads, train depots, and towns were patrolled by armed guards who decided who could enter, who could meet, and what they could do or say. To defy the guards or to even hint at union sympathy was to invite a beating, exile, or even death. Constitutional guarantees such as freedom of speech and freedom of assembly were strictly denied.

To the miners and mountaineers this arrangement became know as the “mine guard” or “Baldwin Felts system” and it became prevalent throughout the southern West Virginia counties of Mingo, Mercer, McDowell, Wyoming, and Pocahontas. Private police forces, paid for by the coal companies, ruled southern West Virginia absolutely and with impunity. Hundreds were deputized by the counties and so acted under the authority of the law with the power to arrest any individual. Their purpose was to keep out the UMWA and they did so with ruthless efficiency. In Logan County guards were unnecessary because its legendary sheriff, Don Chafin, ruled his kingdom with an army of over three hundred deputies whose salaries were also paid for by the coal operators. For his efforts, Chafin received a royalty on every ton of coal mined in Logan County.

In 1912, the coal operators on Paint Creek refused to renew their contract resulting in a strike by the miners of Paint and Cabin Creeks. The operators imported hundreds of guards who evicted thousands of miners and their families and who then began a brutal campaign of intimidation and terrorism against them. The miners, who had experienced the brutality of the guards on Cabin Creek, were prepared and began fighting back. The level of violence grew resulting in three declarations of martial law. Among the more notable events was the running of the “Bull Moose Special,” an armor-plated train outfitted with machine guns which the operators used to spray a miners tent colony at Holly Grove. Adding insult to injury, military tribunals were set up under martial law and in violation of the state and national constitutions to try miners accused of various offenses. Many were sentenced to prison including the famous labor activist Mother Jones who was sentenced to twenty years for reading the Declaration of Independence in public. Eventually the new governor, Henry Hatfield, forced a settlement but the miners, angry at the continued presence of mine guards, defied the governor and forced full recognition of the UMWA.

In 1914, the union organized the New River fields and in 1916, the Fairmont field. By the end of World War I, well over half of the state was unionized and so in the spring of 1920, the final effort to organize the southern fields began in Mingo County. Within weeks, thousands of miners had joined the UMW. In an effort to reverse this development, the coal operators again began importing hundreds of mine guards. When Baldwin Felts agents defied Sid Hatfield, police chief of Matewan, and evicted miners within his jurisdiction, a gun fight broke out between the detectives and Hatfield who was backed by miners and citizens. As a result, seven guards, two miners, and the mayor of Matewan were killed. Hatfield became a hero to the miners but on August 1, 1920, he and an associate were assassinated by Baldwin Felts Deputies on the steps of the McDowell County Courthouse.

This event sparked one of the most remarkable events in American history, the 1920 miner’s rebellion in which roughly 15,000 men armed themselves and began marching south with the avowed intention of overthrowing the governments of Logan and Mingo Counties. President Harding sent Brigadier General H.H. Bandholtz to assess the situation and also dispatched General Billy Mitchell and a squadron of bombers to Charleston, the only time in U.S. history that air power has been deployed against civilians. The miners army eventually faced off with a force of 5000 men, organized by Sheriff Chafin, at Blair Mountain where they were subjected to machine gun fire and bombs dropped from aircraft. After three days of fighting during which perhaps two dozen men were killed, federal troops arrived and the miners broke off the engagement hoping that at last, the mine guard system would be ended. Instead, in only four days, Logan authorities indicted nearly a thousand individuals on various charges including twenty four for treason.

Charles Town was chosen as the venue for the trials. Approximately 800 men were brought here to face charges and on April 22, 1922 Bill Blizzard became the first to be tried for treason. The trial was a national sensation with dozens of reporters from around the country in attendance. Most, like the local citizenry, were sympathetic to the miners. The New York Times observed that “constitutional guarantees…have been suspended by a conspiracy of non-union operators,” and the New York Herald added that West Virginia’s government had “broken down” and its power had “passed… to the coal operators.” On May 27th, 1922 the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. Blizzard was carried through the streets of Charles Town by joyous miners and their ranks, swelled by local citizens, soon formed into an impromptu parade. In the next trial, the Reverend J.E. Wilburn and his son were both found guilty of murder as the result of a gun battle on Blair Mountain and in August, another miner, Walter Allen, was tried and convicted of treason. By this time, the town had become weary of the distractions caused by the trials so the rest of the defendants were given a change of venue.

The choice of Jefferson County as the site for the trial determined that juries that were generally southern and agrarian in character would pass judgment on insurrectionists who had been battling the oppression and exploitation of northern industrialists. The farmer jurymen of Jefferson County acquitted themselves well in their duties. If one accepts the view that the West Virginia Rebellion was not just a fight for union recognition but a struggle for human and constitutional rights, then the significance of the 1922 treason trials changes from interesting and colorful history to something much more important. Further, when compared and contrasted to the John Brown trial, the historical significance of those events and of the Jefferson County Courthouse and Jail compares favorably to any historical site in the nation. Consider these facts. The John Brown trial marked the beginning of the largest insurrection in US history, the Civil War. The Bill Blizzard trial marked the end of the second largest insurrection in American history, the Miners’ Rebellion. Both were fought in defense of constitutional and human rights. In the first trial, John Brown was charged with treason against the state of Virginia. In the second, Bill Blizzard was charged with treason against the State of West Virginia. In the first trial, John Brown stood in opposition to the tyranny and oppression of southern agrarian interests. In the second trial, Bill Blizzard stood in opposition to northern capitalists. In the first trial, John Brown was found guilty and hanged. In the second trial, Bill Blizzard was acquitted and released. Despite the outcome of the first trial, John Brown’s cause was won. Despite the outcome of the second trial, Bill Blizzard’s cause was lost. It is an incredible story.

In 2000, Shepherdstown drew the attention of the entire world as it hosted the latest round of the U.S. brokered Israeli-Syrian peace talks. The talks included Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk al-Shaara. President Bill Clinton served as mediator. The talks did not produce any conclusive agreements, but they represented an important step toward peace.

Present-day Jefferson County is area of change. Developers, attracted by low land prices and flexible city and county zoning regulations, are converting once bucolic rural landscapes into housing developments to accommodate a growing influx of immigrants, many from the Washington metropolitan area. Yet with this change comes a realization that many of the historic resources of the county deserve protection if the county’s rural heritage is to be preserved. Recent surveys by the county’s historic landmarks commission have documented over 1,700 historic structures, many more than 200 years old, and many belonging to prominent Americans of the colonial and post-revolutionary eras, such as the seven homes established by members of the Washington family.

21st century

The New Millennium