Avenue of Invasion

Following the path of Lee’s 1862 Maryland Campaign in Jefferson County.

Download the PDF brochure here.

Lee's 1862 Maryland Campaign

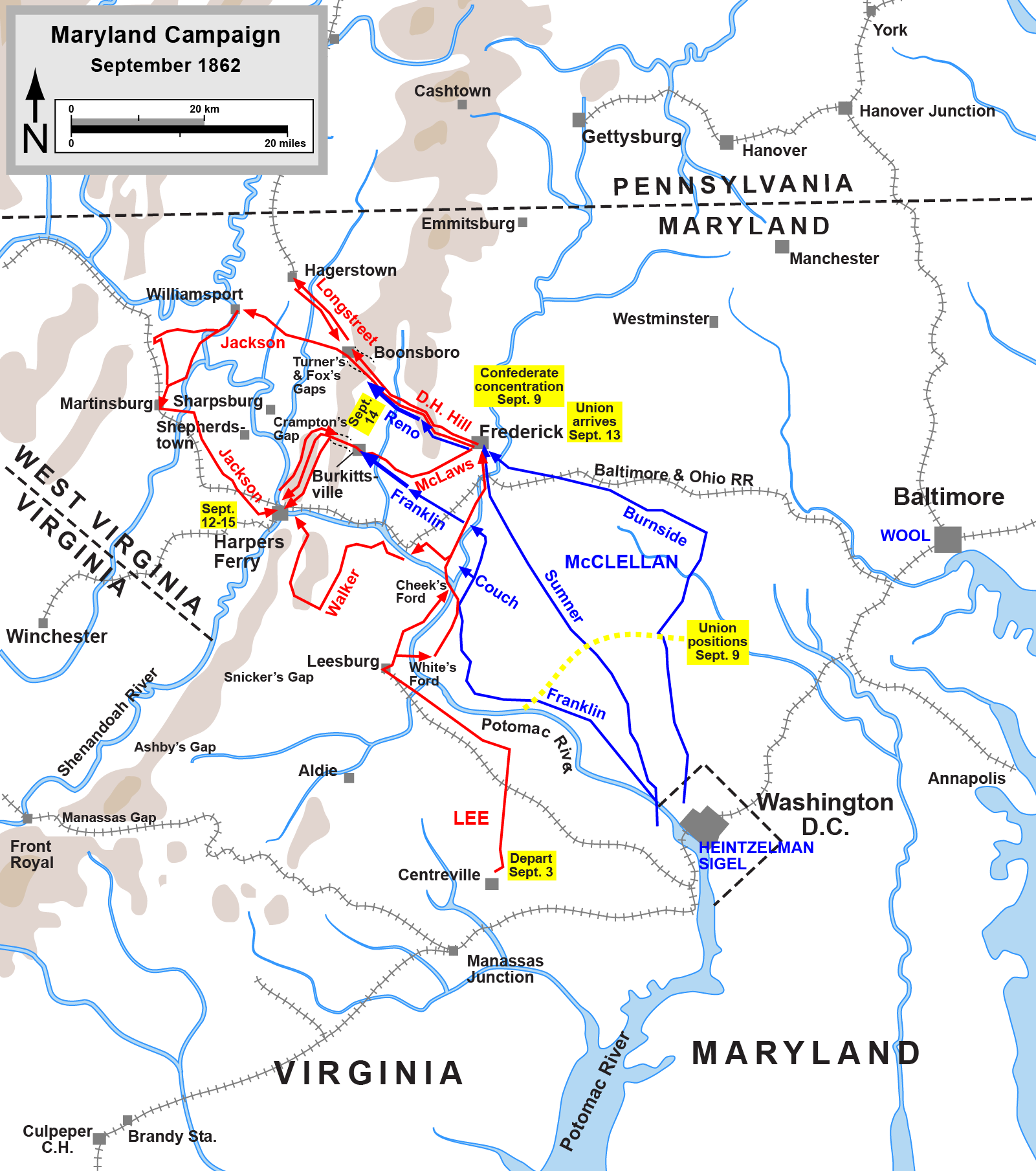

Following a successful spring and summer, Confederate Commanding General Robert E. Lee took the Army of Northern Virginia to the North. Having won a decisive victory at the Battle of Second Manassas, Lee knew he could not remain in Northern Virginia long. His army badly needed supplies and he saw an invasion of the North that was in a state of disarray, politically and militarily, as a way to capitalize on previous successes. Lee convinces Confederate President Jefferson Davis that Richmond will remain safe if he moves his army north. Additionally, Lee hopes that moving north will allow the resources to be fully harvested in the Shenandoah Valley, enabling his army to be better supplied long term.

On September 9th a copy of Order No. 191 from Robert E. Lee was found by a Union soldier in a meadow outside of Frederick, Maryland. The “Lost Order” as it became to be known detailed the Confederate General’s plans for the upcoming campaign, and provided newly reappointed Commanding General George McClellan with detailed insight into Lee’s strategy. Obtaining the order also allowed McClellan to recognize that Lee had divided his army, sending General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson to Harpers Ferry to capture the Federal arsenal there. McClellan failed to decisively act on the information to gain a full advantage, but did ultimately realize he could split the Confederate Army by attacking Lee’s force near South Mountain, Maryland. Hence, the Maryland Campaign began in earnest, and would ultimately lead to the single bloodiest day in American military history. In midst of this critical period of the War, Jefferson County would become central to the operations and hopes of both North and South.

The Lost Order

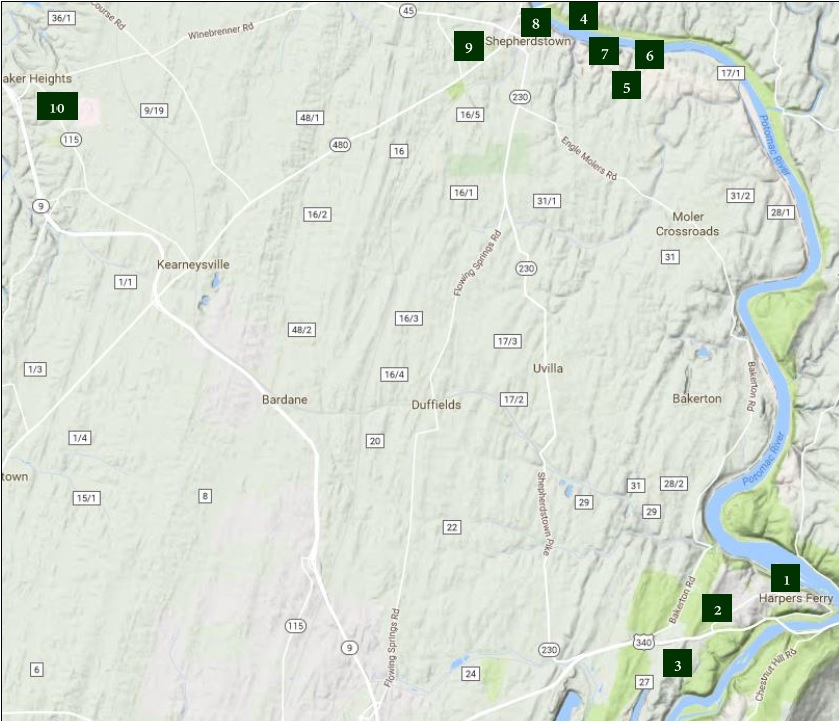

Tour starting point: Potomac Street, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Start at the ruins of the US Armory Site in Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, located on Potomac Street

Stop 1 – US Armory

As Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia advanced into Maryland in the fall of 1862, Lee could not allow his army to be threatened by a Union force at Harpers Ferry. Where you stand are the remains of the US Armory buildings at Harpers Ferry. Construction of the “United States Armory and Arsenal at Harpers Ferry” began in 1799. Though the complex was damaged greatly when it was burned in 1861. A garrison of 14,000 Union soldiers under Col. Dixon S. Miles occupied the town in September 1862.

Following the tour: Head southeast on Potomac Street which becomes Shenandoah Street when you turn right. Go less than 1 mile and turn right onto US-340 South. Go 1 mile turning right US 340 North ALT/ West Washington Street. Take the first left onto Whitman Avenue.

Stop 2 – Bolivar Heights

Confederate Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s division left Lee’s army at Frederick, MD on Sept. 10 and fighting began on September 12. Jackson coordinated an attack that began with artillery placement on Maryland Heights, aimed for an attack against both Bolivar Heights and Camp Hill. On September 13, Jackson’s brigade was about three miles south of Bolivar Heights. Now surrounded on three sides, Miles wrote McClellan that if the garrison was not supported within 48 hours, he would have to surrender. On September 14, Gen. A.P. Hill’s division marched on Miles’s position on Bolivar Heights, where you stand.

Following the tour: Exit the Bolivar Heights parking lot back toward West Washington Street. Turn right onto West Washington Street returning to US-340 South. Go 1 mile and turn left onto Millville Road. Enter the NPS parking lot on your right after 0.5 miles.

Stop 3 – Jackson’s Flank Attack

After the success of Hill’s attack on Bolivar Heights and with the high ground surrounding Harper’s Ferry in his possession, Jackson ordered additional artillery to be brought up that evening in preparation for an assault on the morning of the 15th. Jackson’s assault included a daring flanking maneuver by Hill’s men on the Federal position here. While contemplating surrender, Miles was mortally wounded by cannon fire. The Federal’s would surrender their garrison, the largest Federal surrender during the war. After paroling the prisoners, Hill joined Jackson, who had left one day earlier, at Antietam.

Following the tour: Turn left out of the NPS parking lot onto Millville Road, go 0.5 miles toward Allstadts Hill Road. Continue on to Bakerton Road, which turns into Engle Molers Road. Go 11.5 miles. Turn right onto Shepherdstown Pike (WV-230) and follow until you reach S. Duke Street. Turn right onto S. Duke St. Go 1 mile. You will cross the Potomac River into Maryland, turning right on to Canal Road. Go 0.5 miles to the parking lot on your left.

Stop 4 – Withdraw into Virginia

The Battle of Antietam still stands as the single bloodiest day in the Civil War. Despite this, the Confederate and Union Armies stood at a draw, staring across the banks of Antietam Creek at each other for a day after the battle. On the night of the 18th, General Robert E. Lee begins to withdraw his depleted army back to the Potomac River crossing east of Shepherdstown known as Pack Horse Ford. Through the night, a long train of men, wagons carrying the wounded and horses cross the shallow ford back into Virginia. Despite being aware of the Confederate movement, Union General George B. McClellan opts not to follow Lee and encourage further damage to his own beleaguered force. The Army of Northern Virginia moves swiftly enough to cross the Potomac and begin its movement southward into the heart of the Shenandoah Valley.

Following the tour: Turn right onto Canal Road toward Maryland-34 West/Shepherdstown Pike, go 0.5 miles. Turn left onto Maryland 34/ Shepherdstown Pike re-crossing the Potomac River, go 0.8 miles. Turn left on to West German Street. Stay straight through Shepherdstown and go 2 miles, West German Street will become River Road as you exit town. Turn right on to Trough Road and go 0.1 miles to a small parking area on the right.

Stop 5 – The Confederate Defense

Following Lee’s successful movement into Virginia, he positions some 600 men, largely artillery on the heights above to your front. Commanded by General William N. Pendleton, the Confederates simply hope to defend the ford and prevent further attacks on its rear as they make their way toward Martinsburg en route to Winchester and southward. Pendleton, a preacher from Lexington and friend of Lee’s, does not expect too much harassment from the Federal troops on the opposite side of the Potomac. However, on September 19th, Federal sharpshooters cross Pack Horse Ford and overrun Pendleton’s position, sending the General in somewhat of a panic in retreat to the main body of the Army of Northern Virginia. The Federals successfully capture four of Pendleton’s forty four artillery pieces, one of which had been captured by Confederates at the Second Battle of Manassas. Despite their success, McClellan passes along an order to General Fitz John Porter to halt the assault and recall his men to the Maryland side of the Potomac. He would wait until the next day to launch a full scale attack on Lee’s rear.

Following the tour: On foot, turn left on to Trough Road back toward River Road intersection. Turn left onto River Road, go 0.3 miles to the Cement Mill ruins on your right. Please stay behind the fence around the ruins.

Stop 6 – The Second Day

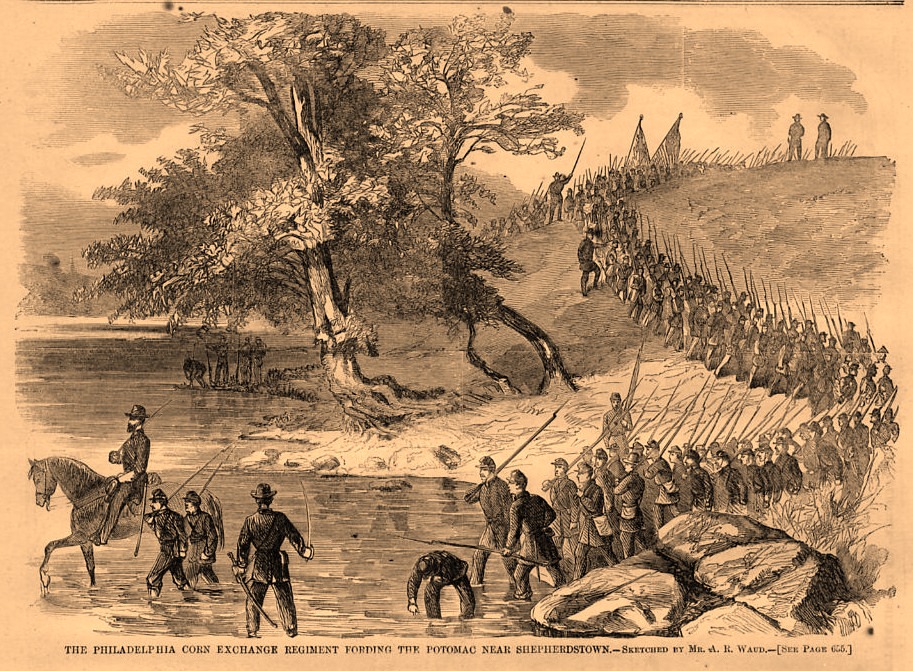

The following morning, on September 20, 1862, General Fitz John Porter orders nearly two divisions back across the Potomac to establish a bridgehead. Having captured the heights above the river crossing, the Federals sought to continue to pursue Lee’s army southward. Having been made aware of Pendleton’s retreat, General Thomas Jackson ordered one of his divisions commanded by A.P. Hill to return to the crossing site and repel the Union advance. While many of Porter’s men crossed the river, Hill’s men attacked Union pickets and launched a full assault under heavy artillery fire on the surprised Federals. They immediately started to withdraw as the order passed to the various units, but the 118th Pennsylvania had crossed a ravine, which separated them from the main body of the army.

Following the tour: Follow the trail around the side of the Cement Mill ruins to the remains of the 6 kilns further up river on the trail.

Stop 7 – The Corn Exchange Regiment

In the face of A.P. Hill’s rapid advance, a courier reached Colonel Charles Prevost of the 118th relaying the order to retreat. Prevost, insulted by the irregular nature of the message, refused and ordered his regiment to stay put. The inexperienced Pennsylvanians had not yet seen live action and nearly half of their rifles were, unbeknownst to them, defective. Despite efforts, the regiment was quickly surrounded and began to be pushed back to the edge of the cliffs above the Potomac. Soon after Prevost was seriously injured in an attempt to rally his men. Soon, the men began to retreat in haste, some of them taking refuge in the six kilns to your front. The 118th would lose 269 men before reaching safety on the opposite bank.

Following the tour: Return to your vehicle and turn right on to Trough Road moving toward River Road. Turn left on to River Road and continue 1 mile to South Mill Street. Turn left onto South Mill Street and go 0.2 miles. Turn right on to East Washington Street and go 0.2 miles. The Shepherdstown Presbyterian Church will be on your left. Street parking is available.

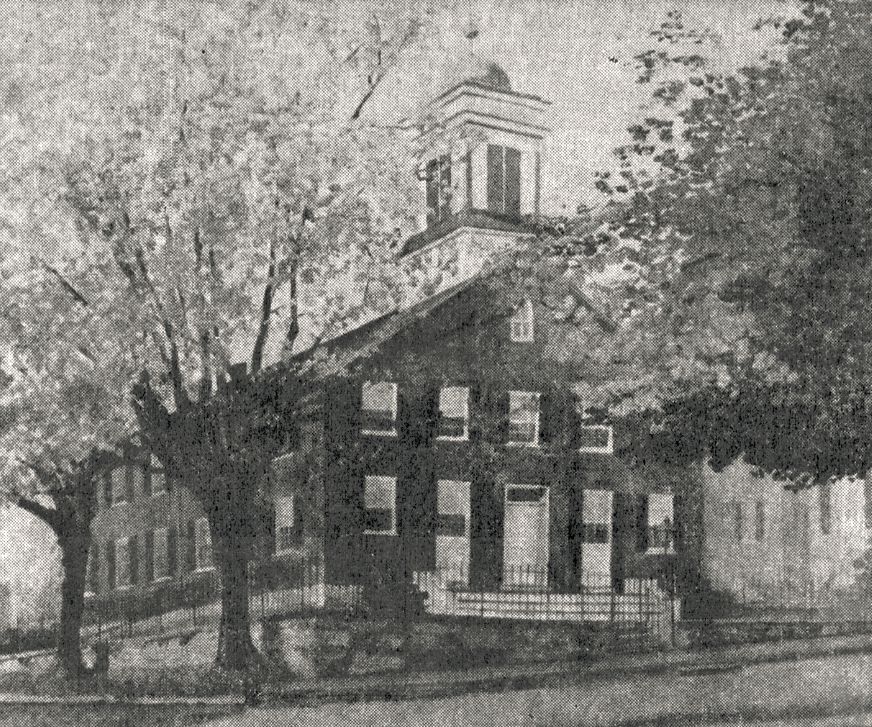

Stop 8 – Caring for the Wounded

In the days that followed the battle, both sides began to tend to the ghastly task of caring for the wounded. Here, the Presbyterian Church served as a hospital for casualties from the previous days of battle, the largest makeshift hospital in town. The residents of Shepherdstown soon became overwhelmed with thousands of walking and gravely wounded soldiers. It has been estimated that at one point, as many as 6,000 wounded sought shelter in the homes and businesses of the town. Mary Bedinger Mitchell, a Shepherdstown resident, wrote of the days following the Battles of Antietam and Shepherdstown saying it was “the most trying and tempestuous week of the war for Shepherdstown.”

Following the tour: Go northwest on West Washington Street toward South Church Street. Go 0.2 miles. Turn left at the second cross street on to West Virginia 480 South/ South Duke Street. Go 0.2 miles to Elmwood Cemetery on the right. Street parking is available.

Stop 9 – Elmwood Cemetery

Here, at Elmwood Cemetery, are the graves of many soldiers who fought in the Maryland campaign. The results of the campaign yielded little headway for either army in the broad scope of the War. The intense fighting which had taken place essentially returned both armies to their respective positions and neither side could claim any significant advantage as a result of the tremendous losses of the campaign. 114 soldiers are interred here at Elmwood who fought in the 1862 Maryland Campaign, most them having fallen on the battlefields you have visited on this tour. Other notable individuals buried here are Alexander Boteler, owner of the Cement Mill and Henry Kyd Douglas, the youngest member of Stonewall Jackson’s staff and a Shepherdstown resident.

Following the tour: Turn right on to West Virginia 480 South toward Cherry Lane. Go 5 miles until you turn right on West Virginia 115, go 1.7 miles until you reach Short Road. Turn left onto Short Road and continue for 0.6 miles. Merge on to West Virginia 9/West and continue for 2.2 miles. Turn right onto Douglas Grove Road, park in the spaces provided for the Route 9 Bike Path on your left.

Stop 10 – “The Enemy has learned their lesson…” In days that followed the Battle of Shepherdstown, both sides tended to their wounded and rested. In less than ten days, the two armies had sustained nearly 30,000 casualties. Here, on the banks of the Opequon Creek, Robert E. Lee’s battered army encamped. Lee now began to realize that he could no longer consider attempting to press in to Maryland again. The Maryland Campaign was over. Alternatively, McClellan also gained resolution from the Battle of Shepherdstown that further pursuit of the Confederate army was too risky. His men had been turned back in their pursuit at Shepherdstown and the disastrous consequences of the 20th had done little to encourage more action on his part. In October, Lincoln visited his general, still situated in Sharpsburg, to encourage McClellan to continue what he started at Shepherdstown on the 20th. The young general’s ultimate refusal to do so would lead to his final dismissal as commander of the Union Army. The campaign did allow for Lincoln to announce the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all slaves in the rebelling states. Yet hopes that this would deter the Confederate war effort were quickly vanquished as the Civil War would rage on for three more years, ultimately leaving more than 620,000 men dead and a Nation forever in remembrance of the historic events of September 1862.

In days that followed the Battle of Shepherdstown, both sides tended to their wounded and rested. In less than ten days, the two armies had sustained nearly 30,000 casualties. Here, on the banks of the Opequon Creek, Robert E. Lee’s battered army encamped. Lee now began to realize that he could no longer consider attempting to press in to Maryland again. The Maryland Campaign was over. Alternatively, McClellan also gained resolution from the Battle of Shepherdstown that further pursuit of the Confederate army was too risky. His men had been turned back in their pursuit at Shepherdstown and the disastrous consequences of the 20th had done little to encourage more action on his part. In October, Lincoln visited his general, still situated in Sharpsburg, to encourage McClellan to continue what he started at Shepherdstown on the 20th. The young general’s ultimate refusal to do so would lead to his final dismissal as commander of the Union Army. The campaign did allow for Lincoln to announce the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all slaves in the rebelling states. Yet hopes that this would deter the Confederate war effort were quickly vanquished as the Civil War would rage on for three more years, ultimately leaving more than 620,000 men dead and a Nation forever in remembrance of the historic events of September 1862.

End of tour.

This tour was produced in a partnership between the Jefferson County Historic Landmarks Commission, the Jefferson County Farmland Protection Board and the Jefferson County Convention and Visitors Bureau. Sources for this tour were referenced from the American Battlefield Protection Program, Thomas McGrath’s Shepherdstown: Last Clash of the Antietam Campaign, September 19-20, 1862, Kevin Pawlak’s Shepherdstown in the Civil War, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Encyclopedia Virginia and the Shepherdstown Battlefield Preservation Association. You may have noticed that many of the areas where these historic events took place are now developed. Preservation efforts continue, but need private support. For more information on how you can help preserve these hallowed sites, visit: www.JeffersonCountyHLC.org

This tour was produced in a partnership between the Jefferson County Historic Landmarks Commission, the Jefferson County Farmland Protection Board and the Jefferson County Convention and Visitors Bureau. Sources for this tour were referenced from the American Battlefield Protection Program, Thomas McGrath’s Shepherdstown: Last Clash of the Antietam Campaign, September 19-20, 1862, Kevin Pawlak’s Shepherdstown in the Civil War, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Encyclopedia Virginia and the Shepherdstown Battlefield Preservation Association. You may have noticed that many of the areas where these historic events took place are now developed. Preservation efforts continue, but need private support. For more information on how you can help preserve these hallowed sites, visit: www.JeffersonCountyHLC.org